Introduction

Resilience has been at the heart of international development discussions in recent years, but competing definitions and sector-based funding streams have hampered implementation, according to expert [Steve Latham] who spoke to Devex.

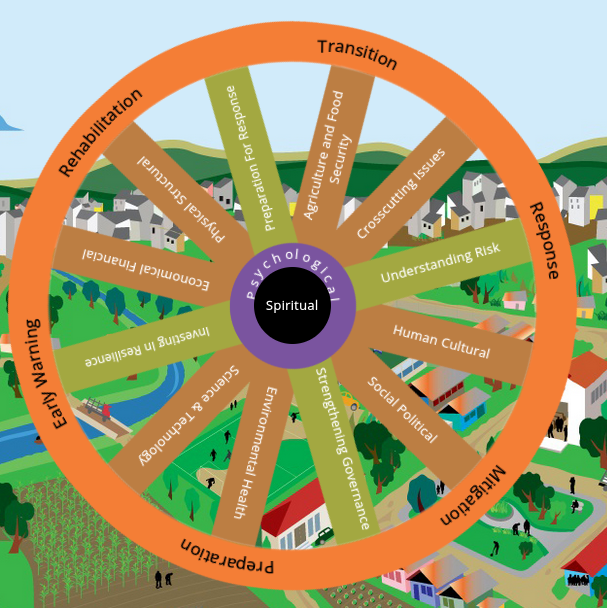

Donors and organizations approach resilience in a fragmented, rather than holistic, way, said Stephen Latham, an instructor at Northwest University’s international community development graduate program. Instead of seeing the big picture, stakeholders might focus on just one piece of resilience — for example, water access or food supply — based on their expertise and funding. Such an approach could still leave vulnerabilities in countries’ abilities to withstand shocks.

“We need to think of resilience as being crosscutting, rather than sectorializing [the approaches to development],” he told Devex. A “multidimensional and multidisciplinary” approach is impossible when different stakeholders focus on isolated pieces of resilience, he said.

Fragmentation is most evident in two areas: defining what resilience really is and translating that idea into programs on the ground.

There is an ongoing debate about what resilience means, and how it should be measured and implemented. The U.S. Agency for International Development, for example, defines resilience as the ability of stakeholders “to mitigate, adapt to, and recover from shocks and stresses in a manner that reduces chronic vulnerability and facilitates inclusive growth”.

Others favor a wider definition, such as that laid out by the Center for Strategic and International Studies to include not just disaster preparedness, but also the ability to withstand financial, political, and environmental pressures.

Latham prefers a broad view, he told Devex. “We live in an increasingly fragile and more unpredictable risk context … so we need to arrive at a global framework for resilience that looks beyond just natural hazards.”

Programs targeting resilience rose in prominence after natural disasters such as Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines in 2013 and the Haiti earthquake in 2010. But resilience could also be applied to conflict situations, civil conflicts, and economic depression, among others, Latham said.

Disagreement over definitions and priorities can lead to fragmented programming on the ground. Latham, who also worked as a resilience and disaster risk reduction adviser for the Latin America and Caribbean region at World Vision, pointed to Haiti as example. After a devastating hurricane hit the country in 2008, humanitarian groups built houses meant to withstand strong winds and rain. But no one accounted for whether the structures could survive high magnitude earthquakes.

“The houses [in Haiti] were built to withstand hurricane force winds,” he said. “But nobody expected the earthquake in 2010. So you had very thick walls and ceilings which were made out of concrete to make sure the roofs would stay in place. But those same walls, when the earthquake struck, were the ones that collapsed over a quarter of a million people.”

Bridging the gaps

Funding streams contribute to a fragmented approach. “There is a reason why we tend to sectorialize resilience programs. It’s because the funding streams are attached to sectors,” Latham said.

Prior to the onslaught of Superstorm Sandy in 2012, for example, some funders and organizations were focused on programs geared toward environmental sustainability, but they failed to account for the damage of the storm, to anticipate even stronger ones, or to address other hazards, he said.

“Sustainability being green isn’t good enough to deal with hazards that are becoming more pronounced and less predictable,” Latham said. “Risk is becoming more complex and our exposure to hazards [require us] to build systems that are more robust … when exposed to all these different adverse events.”

Breaking down funding silos is vital in building resilience, he said. One example comes from the potential benefits of climate-proofing all development programs instead of just those dealing with environment and climate issues.

Latham said a more holistic approach to project design and funding should take into account all hazards, vulnerabilities and risks, in an attempt to minimize errors such as in the case of the houses in Haiti.

Development stakeholders will also need to collaborate and cooperate to make sure that their programs do not overlap but instead reinforce each other, he said.

“The way the programs are funded are very much focused on sectoral approaches … we’re like focusing on the tree at the expense of the forest,” Latham said.

Fragility to resilience

One way to help bring stakeholders together could be to focus on the capacities and potential of countries’ preparedness, rather than simply highlighting fragilities.

“It is interesting that fragility is gaining so much traction when its flip side is resilience. Some countries are characterized as fragile state and they don’t like that title being played on them,” Latham said.

“When you put a label on them, I think it’s much more likely to influence [them] and to have an impact if you’re accentuating the positive effect like their capacity or competency,” he added.

No matter their approach, keeping the end goal in mind is key, Latham said. Development stakeholders should remember that their programs should be “designed to bounce back better to absorb the shocks and to enable [individuals and communities] not only to survive but also to thrive in the face of adversity.”

Author: Lean Alfred Santos, DevEx reporter

Source of original article: https://www.devex.com/news/fixing-the-fragmented-approach-to-resilience-87950

Yours on the journey towards resilience,

Steve